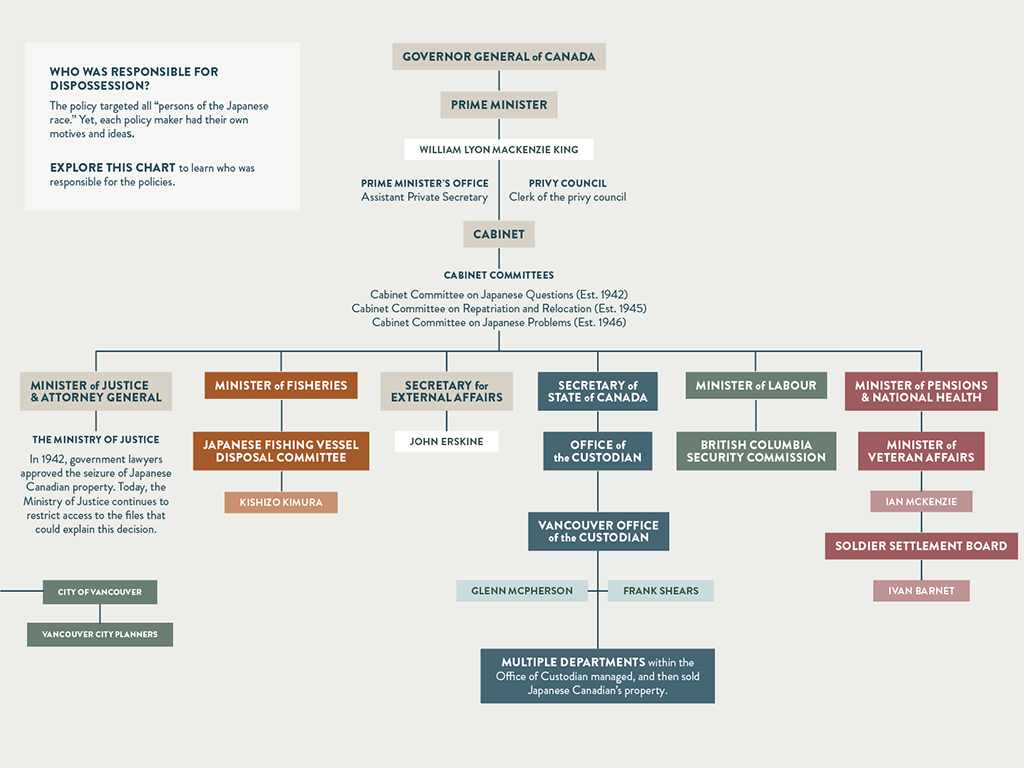

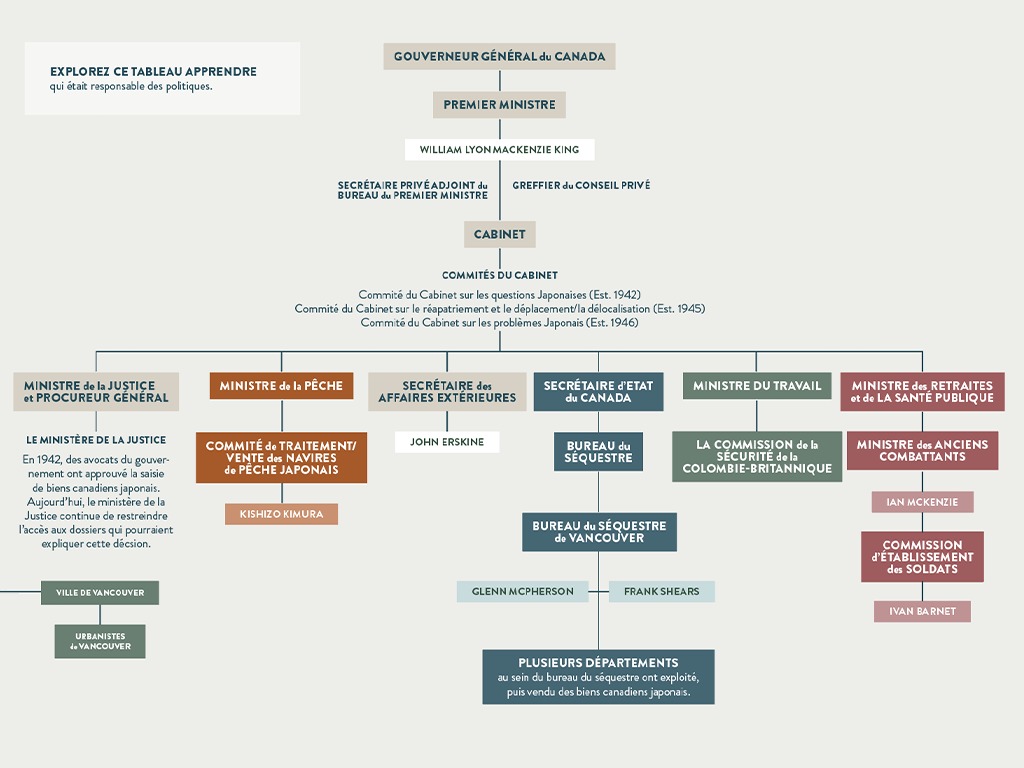

Who Broke the Promise?

Large-scale injustice requires many hands

People made dispossession happen. Politicians signed it into law. Senior officials decided the details. Local agents put policy into practice.

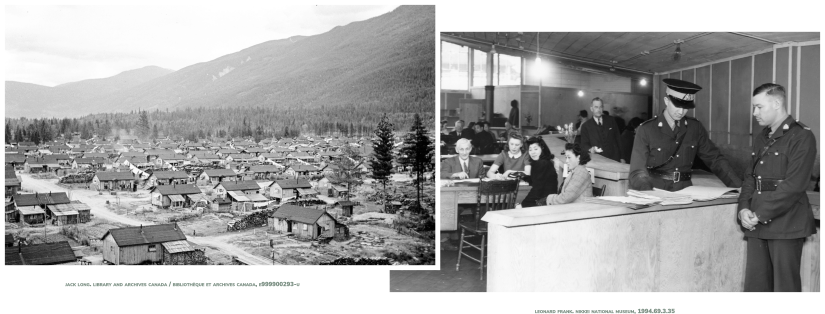

Imagine warehouses of furniture, clothing, musical instruments, and books.

The Custodian of Enemy Property, a federal office, controlled everything Japanese Canadians were forced to leave behind. By 1942, 120 employees worked in Vancouver’s Royal Bank Building, filing documents and cataloguing belongings.

Real estate agents inspected houses. Government workers priced farms. Auctioneers chanted bids to thousands of eager buyers.

City Real estate

City of Vancouver officials saw an opportunity when the internment began: the historic Japanese Canadian neighbourhood on Powell Street could be demolished and replaced with modern housing. This plan helped to convince the federal government to sell. But the proposed redevelopment never happened.

fishing boats

In January 1942, the government formed a committee to encourage fishers to sell or lease their vessels. When some Japanese Canadians refused to sell, the Committee forced them. Years later, government lawyers publicly admitted that the sales were illegal, but buried the issue.

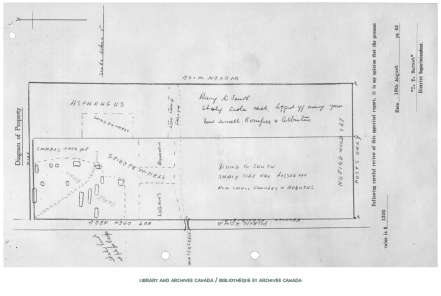

farms

Most Japanese Canadian farms were sold to the Director of the Veterans’ Land Act in 1944. These 769 farmlands were deliberately underpriced by officials. They wanted the lands to benefit soldiers returning from war.

Family heirlooms

Some friends and neighbours saved the personal belongings of Japanese Canadians, returning them when they could. Most, however, looted and stole. Rather than stop the looting, the government decided to sell what remained. Between 1943 and 1946, it held 255 auctions and sold over 90,000 belongings.